In a previous blog, we highlighted similarities between marketing and change management and suggested six questions that can serve as a foundation for successful change management initiatives. Taking one step further, here we look at the similarities in the communication requirements of these two disciplines that will be increasingly critical in both the pandemic response and next phase of economic recovery.

In his hit song, Mirrors, Justin Timberlake sings of the way his love is the other half of him, completes him, and supports him. The song is great, but its relevance here is in the way his words perfectly capture both the similarities between marketing and change management and the way that understanding those similarities can make each discipline better.

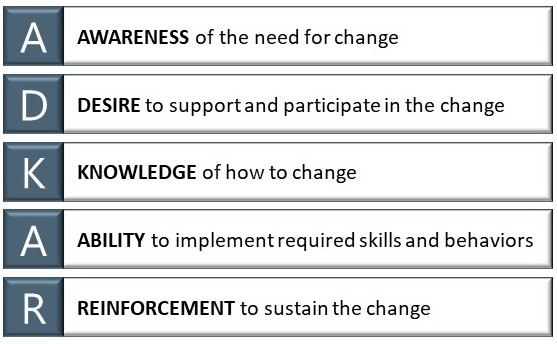

In change management, ADKAR is a widely known and respected methodology. The letters represent the journey through which change managers must guide their audiences in order to achieve the desired new state.

The value of a framework like this is that it identifies all of the moments in the journey that need to be accounted for and addressed through communications and training. It also enables a leader to think strategically about where the biggest risks and opportunities for influence lie. For example, if a company is introducing a new software application to replace a much despised legacy system, the opportunity to drive change may be greatest in the Knowledge and Ability stages: nobody needs convincing that the new system is better than the old but they may need extensive guidance on how to do their jobs under the new system. Conversely, the introduction of a new process for customer onboarding that is projected to save money and increase retention may require more emphasis on building Awareness and Desire if the current process, to those using it every day, doesn’t seem “broken.”

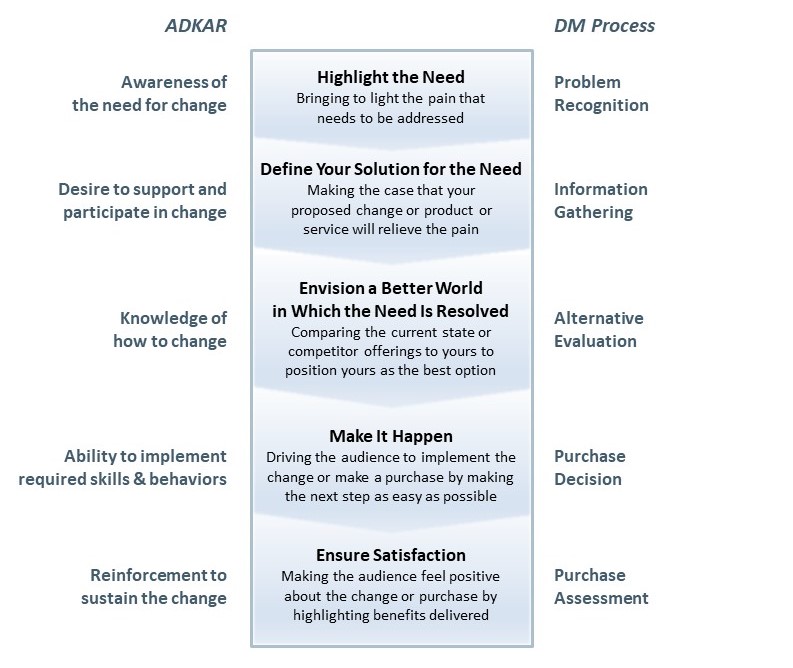

In marketing, the customer decision-making journey is often defined through the following stages: Problem Recognition, Information Gathering, Alternative Evaluation, Purchase Decision, and Post-Purchase Assessment. As with the ADKAR framework, this model enables leaders both to think carefully about each stage of the process and to identify the stages in which the flow is most at risk. For example, a new entrant to the CRM software market may need to invest heavily in the Information Gathering and Alternative Evaluation stage in order to gain consideration by prospective customers. On the other hand, a company selling a new kind of service connecting corporate art buyers and artists may need to focus on Problem Recognition to drive prospects to consider their solution.

Interestingly, when we line these two models up next to each other, it is, in the words of Justin Timberlake, like each is “lookin’ at the other half of” the other. More importantly, the alignment brings to light the key objective in each of the five stages.

A subsequent blog post will provide more guidance on how these objectives can provide a powerful foundation for devising more effective change management communications, but to illustrate the potential:

- The objective to “highlight the need” drives home that the efforts to build awareness of the need for change must be from a credible source and be seen as empathetic.

- The objective to “Envision a better world in which the need is resolved” makes it clear that any attempt to build knowledge of how to change requires that the “how” be seen as irresistibly simple and clearly puts the better, future state close at hand.

- Focusing on the objective to “Make it happen” will ensure that assertions of the audience’s ability to implement will minimize friction and build confidence.